When the pandemic hit in 2020, Karen Lee Orzolek set about constructing what she thought of as a “portal” in a closet at the foot of her stairs. Orzolek, better known as Karen O, the spectacularly charismatic frontwoman of Yeah Yeah Yeahs, was experiencing the locked-down contraction of her world along with everyone else. Unlike everyone else, however, Orzolek is a rock star in the truest sense of the word – a woman used to selling out huge venues with a triple-Grammy-nominated band whose driving spirit these past 22 years comes from a swirl of notions that now seem almost antiquated: that rock music might set you free, that defiance can change the world, that transcendence through art is possible.

Remembering that odd year spent at home in Los Angeles, Orzolek, 43, thinks first of worms: “My son was really into worm-hunting in our backyard; I remember life shrinking down to going on worm hunts with him,” she says with a smile. Second, she thinks of the concerts she did in that closet, mini broadcasts over Instagram for which she would transform her tiny space into “a different world” each time. Balloons, streamers, whatever it took – the band’s gleeful DIY spirit prevails.

Those peak-pandemic months were the first time since she was a child that Orzolek experienced time as irrelevant: “Isn’t it so fascinating how these fraught times can bring so much revelation?” Now, nine years after the last Yeah Yeah Yeahs record, that sense of revelation thrums through their triumphant fifth album, Cool It Down. Finely calibrated between widescreen emotion and sonic precision, it sounds ready to sweep the jaded out of their stupor, and is the band’s best testament yet to their idealist spirit.

It is mid-May, and Orzolek has arrived early to the sun-drenched terrace of a Los Angeles hotel wearing a sky-blue jumpsuit that makes her look like a chic garage attendant. A stylish older woman leaps up from a neighbouring table to tell her it’s incredible: did she make it herself? Orzolek thanks her and tells her no, her best friend did. This is designer Christian Joy, whose outre costumes shaped the band’s iconography from the start. By phone, Joy recalls the first one she made for Orzolek: “It was this really ugly, shredded blue prom dress that said ‘Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ all over it and had all these plastic flowers hanging off it. It was ugly and she rocked it.”

In September 2020, Orzolek once again enlisted Joy. The band were turning 20 and Orzolek wanted to celebrate with a closet performance that would be some sort of transmission of love. For this, she needed an outfit that recalled the messy exuberance of their 2003 debut album, Fever to Tell. The concept, Joy says, went something like: “Crazy mom at a kids’ party who’d walked away with the whole table.” She sometimes wonders when Orzolek will “reach the point where she’s like: ‘OK, I can’t wear this stuff any more.’ I mean, we’re all in our 40s now …”

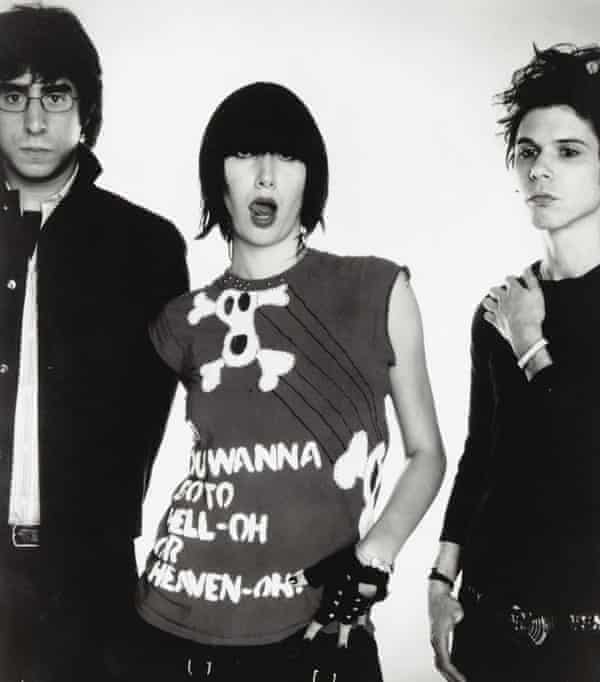

In the clip, Orzolek appears against a backdrop of shiny rainbow streamers, wearing a spangly headdress bristling with balloons and a dress made from a shower curtain studded with dollar-store party tat. Then, with drummer Brian Chase and guitarist Nick Zinner beamed in via video, she sings their most indelible love song, Maps. It seems a sweet irony that a band known for not giving a damn should have this raw-hearted distillation of longing be their most famous song. Yet both Maps and the carnival-like disinhibition of the live shows seem to come from the same source: a refusal of self-consciousness.

Zinner is next to arrive on the terrace: pale, clad in black, and wincing from the sun, he murmurs drily about being “a diva” as he seeks the shadiest corner of the table. His demeanour, that of a bewitched Tim Burton character, makes him an endearing foil to the labrador-like enthusiasm of Chase, who pulls up a chair with an: “All right! Los Angeles!” Chase, 44, is the lone NYC holdout; Orzolek moved to LA in 2004, and Zinner, having gone back and forth between the two cities, finally moved in 2020. People still assume, Orzolek says good-naturedly, that they all still live in New York.

As much coffee and kale is ordered, I sense the magnitude of these three people having known each other for so long. “When we started out in 2000 we were inspired by music that came out in 1980,” says Zinner in quiet wonderment. “You know, ESG or New Order … and I can’t wrap my head around the fact that the beginning of our band is the mid-point between those things.”

Both Chase and Orzolek are parents now, yet all three still seem like the awkward, occasionally awestruck art-school kids who came together in New York. When I suggest that silliness is at the band’s core, Orzolek agrees seriously, then gazes at the table to let a thought coalesce: “God, give me a second because this is huge …” Still thinking, she offers a throwaway line: “Don’t take the tongue out of the cheek!”

“Did you just come up with that?” says Chase, impressed. “That’s brilliant.”

She laughs this off. The creative ideal, for Orzolek, is “if you can forever be in the sandbox. For one thing, it’s disarming.” This was something she tried to figure out in the band’s earliest days. “I mean, New York’s a tough crowd. It’s a lot of somewhat jaded people who’ve seen it all.” It was a question, then, of: “How do I disarm this crowd of their own self-consciousness?” The answer was by summoning a welter of sexuality and absurdity and angst, ridding herself of self-awareness. “It sets me free! And the idea is if it sets me free, it sets everyone else free. And it sets Brian and Nick free! I mean, holy shit, the three of us when we’re up there: it really does feel like radical freedom.”

“Performing with this band,” Zinner says simply, with full eye contact, “is the greatest thing in the world.”

After the release of 2013’s Mosquito, however, it was by no means certain there would be another Yeah Yeah Yeahs record. The band had fulfilled their contract with Universal and thus freed from a cycle of writing, recording, touring. A couple of years later, Orzolek had a son, Django, with her husband, Barnaby Clay, a director. “I’m glad I was able to squeeze one out,” she says. “And then I was rubble for a couple of years after that.” The band remained in close touch but it wasn’t until late 2019 that they started talking about new music. In early 2020 came what they refer to as “the Black Dragon conversation”.

“Karen and I had dinner and were hanging out and drinking this sake called Black Dragon,” Zinner explains. It resulted, Orzolek says, in the worst hangover of her life. But that night was also the first time she expressed a readiness to start writing again.

“They’ve been extremely patient in waiting for me to come round,” she says of her bandmates. The Black Dragon conversation acknowledged the trauma of the Trump years, plus “the baggage and pressure of just 20 years of being a family”, ultimately leaving all three with one governing question: “How can we do this in the most joyful, pressure-free sort of way?”

Soon after Zinner sent Orzolek a folder of ideas, the pandemic arrived. Not long after that, wildfires began raging through LA and Orzolek was reminded of “this ticking clock” of ecological doom. Confused by hearing so much music that seemed merely escapist, she longed to hear her emotions reflected – not least the vertigo of parenthood, and “ushering a new life into a world that feels so uncertain”. The mood of the album’s first track, Spitting Off the Edge of the World, is one of defiance – in particular, “defiance of ruin. It was me wanting to convey to my child that all’s not lost.”

“There’s what I describe as a zoom-in, zoom-out quality to living right now,” says Chase. “The more I zoom out, the more I realise how problematic life is. Which sphere do I place myself in? Do I keep things in the immediate, or how much do I obligate myself to concern with the larger circumstances?”

“I’m just stumbling through that every day,” says Orzolek. “In order to write music you have to be great friends with mystery and uncertainty. When Nick and I initially go in to ‘jam’ or whatever, we have this affinity and trust with the mysterious process of how music arrives. You have to be so open and almost innocent. I know I’m good at it when it comes to making music in this band – that’s the safe haven for big feelings.”

The songs flowed out faster than ever before, with Orzolek seized by an urgency she hadn’t experienced since Fever to Tell. The result is a bombastic studio record, conveying a sense of cosmic awe with a punk sneer: when guest artist Perfume Genius sings on the euphoric opening track about the sun “melting houses of gold”, it’s both a spitting “fuck you” to capitalist greed and an arms-wide “I love you” to our planet. Cool It Down is also, Orzolek notes, “the most peaceful record between Nick and I – it just felt so simpatico”.

“Just to see these things emerge from Karen, seemingly instantly …” murmurs Zinner, “it was so cool.”

Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ very first show in 2000 was as the first of three openers for a little-known outfit called the White Stripes. “To play a show at the Mercury Lounge, to play a show in New York City – that was it!” says Orzolek. Beyond that, they had little or no ambition. “I don’t know if the Strokes did, or anyone did. Everyone was just doing it because they wanted to do it; it just happened to be the right place at the right time.”

The grimy, heedless glamour of that moment is now undergoing a resuscitation. There’s the forthcoming documentary adaptation of Lizzy Goodman’s oral history Meet Me in the Bathroom, which memorialises the rise of Yeah Yeah Yeahs and their cohort – the Strokes, LCD Soundsystem, TV on the Radio. We are also witnessing the so-called “indie sleaze” revival, whereby all the sweat, glitter and spilt beer of an early 2000s subculture is being reclaimed by a generation who weren’t born at the time: Orzolek and her iconic bowl cut feature prominently on the Instagram account indiesleaze. When the US songwriter Lucy Dacus (of Boygenius) first heard Yeah Yeah Yeahs in high school, Karen O “opened up a world of possibility,” she tells me. Dacus was seized by Orzolek’s “wild confidence … her showing up in a way that felt reserved for rock legends. She was like, ‘Actually I’m a rock legend.’”

There are, Orzolek will readily admit, two different Karens: the self-effacing one at this table, just a shy girl from New Jersey, and then the onstage force that is international rock goddess Karen O, howling and yelping into a mic.

“I really revelled in there being little to no precedent or legacy for me,” she says. “I felt like because there are so few [women] and they’re all fucking crazy mavericks – Janis Joplin, Grace Slick, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry – all they taught me was you make it up as you go along. So I felt incredibly liberated in that sense.”

It is one reason she felt fairly unscathed by the sexism of that time. “But yeah, the shots up the fucking skirt … That sucked.” It also annoyed her that people paid more attention to the spectacle than to the songwriting. “I was a hot mess, man,” she says. “The amount I wanted to please the crowd through self-destruction was escalating and escalating.” After she fell off a stage in Australia and injured herself in 2003, “I really had to reconfigure the way I performed. I had to understand that I didn’t need to destroy myself up there in order to reach some sort of transcendence.”

On the band’s forthcoming tour, they will be supported by Japanese Breakfast, whose songwriter Michelle Zauner is Korean-American, and youthful punk band the Linda Lindas, who identify as half-Asian, half-Latinx. Orzolek, who is half Polish-American and half-Korean, is gratified by the “Asian-American representation blossoming” in music. “I feel like I’ve been waiting all my life for that. It’s crazy, man, how things like that change all of a sudden.”

It is also life-affirming in a different way, she adds: “It feels like, ‘Man, we’re cool enough for these cool bands to open for us!’” The astonishment in her voice goes some way, I think, in explaining Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ enduring coolness – because what’s cooler than wonder? Here are three people still not taking a thing for granted, whether it’s worms or the vast mysteries of the creative process.

Now, ahead of their shows for Cool It Down, Orzolek is puzzling over how she might “arrive as who I am right now in this moment” – with vulnerability and courage. “There’s going to be a new performer up there,” she says. “I just haven’t met her yet.”

www.theguardian.com

George is Digismak’s reported cum editor with 13 years of experience in Journalism