Tthe King of the Chitlin ‘Circuit. The hardest-working man in show business. The funniest man alive. These are just three honorary titles awarded to Bobby rushand dresses them all with joyous pride. Rush had planned to start the new year with two London appearances until Omicron canceled his entire European tour, but relaxing at his home in Jackson, Mississippi, the 88-year-old radiates bonhomia. Covid-19 has already greatly disrupted his life, forcing a man who, until 2020, spent the last five decades working more than 200 nights a year, to take a break. Did you relax? Rush laughs: “Sure you do. I went to work in my home studio cutting new material. “

This was after he recovered from the coronavirus. “I was the first person in Mississippi to get Covid,” says Rush. “It was before they gave me the vaccines and I got very sick, hospitalized for five weeks. I survived thanks to the grace of God and the fact that I have always stayed in shape, I have never touched drugs or alcohol. But it sure hit me like never before. “

Rush 2021 Autobiography I’m not studying anymore details this and many other scratches in an epic American life. Considering that he started acting at age 13 and released his first album in 1964, what’s most notable is a work ethic that has seen him win more acclaim and audiences in recent years – he won the Grammy Awards in 2017 and 2020, appearing in the Eddie Murphy film Dolemite Is. My Name and joining Queens of the Stone Age on stage, like never before. Unlike John Lee Hooker and Johnny Cash, who were successfully repositioned in their twilight years, Rush never enjoyed early fame. Instead, his growing audience is solely due to his skill as an animator. “People love my show because I emphasize the good times,” he says. “I encourage people to wear a smile, not frown.”

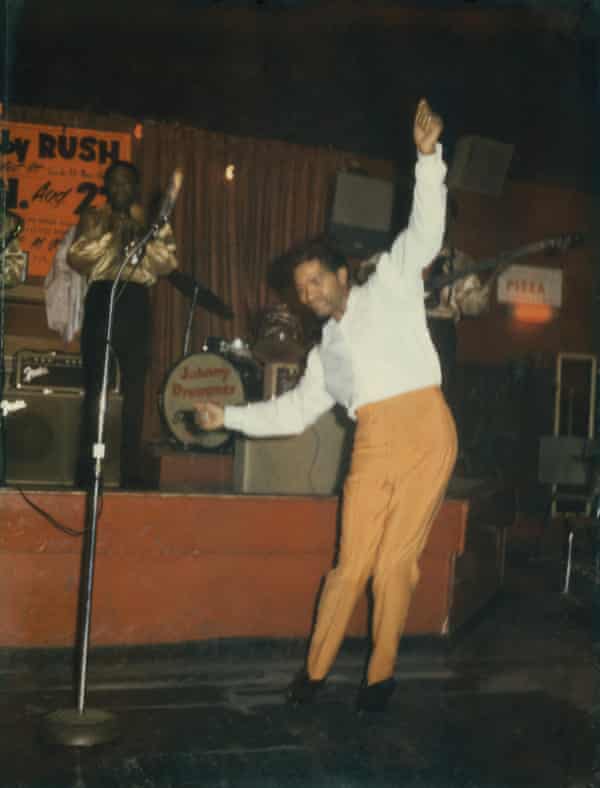

Rush describes his show (or “magazine”) as “black vaudeville” – song, dance, storytelling, often raunchy humor – and these elements provided the key to his breakthrough: The road to MemphisThe 2003 documentary that was easily the strongest effort in Martin Scorsese’s The Blues series, and followed Rush as he worked, his personality and performances won over new listeners. Add to this a new manager with a vision for how to move Rush forward and entered his 80s doing better business than ever.

“I didn’t want anyone to read the book and feel sorry for me,” says Rush of a life in which he was shot, imprisoned and seriously injured when his tour bus crashed and, most punishingly, he lost three of his children to sickle cell anemia. Musicians helped him on the difficult road to success, but James Brown, both when Rush was a junior and later a veteran, left it out of his pocket when he offered generosity. “Some men behave like dogs,” says Rush. “My thing has always been not to give up, to keep pushing, as Curtis Mayfield sang. All those hills and valleys that I’ve climbed, well, someone would always come and take me out. Life is so short that I consider the good as the superimposition of the bad. “

Born Emmet Ellis Jr in Homer, Louisiana, to sharecropper parents, segregation overshadowed very poor upbringing. “We had no electricity in our house,” says Rush. “Just an outside bathroom. I grew up picking cotton and received little schooling. But Mom and Dad loved us and raised us well and even though they had very little money, they made sure we got the essentials. It’s the oldest black blues song in America, and it’s still a road. “

Emmet Jr decided to make his own way at age 13, leaving home to work full time as a farm laborer. Determined to perform, and being tall and confident, he began to sit with blues musicians who played juke venues (shanty bars often built on plantations). At age 15, he joined the Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels company as a singer and dancer, applying burnt cork to his face (as was then expected of minstrels) before performing.

“Bessie Smith and Louis jordan and many others started with minstrels ”, he says. “Minstrels also created black vaudeville, and Sammy Davis Jr and others grew out of that. I’m not defending minstrels, I’m just saying it was a bridge for many of us to enter the entertainment industry. “

He changed his name to Bobby Rush, out of respect for his father, who was now a preacher and blues was considered the devil’s music, working at music venues where sharecroppers drank and danced. Upon moving to Memphis, Rush befriended Rufus Thomas and Albert King and educated him in the basics of the music industry, and then in 1953, he joined the great migration of African Americans north. In Chicago, he earned a reputation for being an entertaining entertainer, but little else: He worked a hot dog stand, opened a barbecue, collected scrap metal, and grafted hard to support his family. Releasing seven 45s on six different independent record labels between 1964 and 1971, it finally clicked when Chicken heads It peaked at number 34 on the US R&B charts. “Folk funk” is how Rush described their sound, and their success became a staple on the jukeboxes of the South, selling a million copies. A bad deal meant he saw no royalties, but it brought him more bookings and the public loved him. “We in the entertainment business,” he says, “so I try my best to do that: entertain. “

Philadelphia International Records signed with Rush and, in 1979, they released their debut album Rush Hour, but it gained little attention. At 46, he refused to resign and continued working in the clubs. An underground star, Rush soon became known as “the King of the Chitlin ‘Circuit” and to many African-Americans, that really is royalty.

“The chitlin ‘circuit is nothing more than a place where black people could go and have a good time,” he says of a flexible network of African-American clubs that offered loyal audiences for people like Denise LaSalle, Latimore, ZZ Hill, Shirley brown and other notable soul / blues artists who never managed to cross white audiences like Al Green, Buddy Guy and Aretha Franklin did. Chicks are deep-fried pig intestines – slavers often gave them slaves after a pig had been slaughtered and made it a staple of “soul food.” Rush notes that they cleaned the shit-filled pig’s colon and seasoned it into a delicacy, “just as we would take old theaters and turn them into an oasis so black people could escape all the shit we were taking from outside.” . world. “While the chitlin ‘circuit spans the US, its stronghold is in the south, and in 1983 Rush moved from Chicago to Jackson, Mississippi, to work on it.

Rush’s folk funk ensures their songs are loaded with country homilies, broad wit, and lustful innuendo: She Caught Me With My Pants Down, Santa Claus Wants Some, and What’s Good For the Goose Is Good for the Gander are funky and lewd. One number, Big Fat Woman, became a comedy trope on the Rush show and has long employed “shake” dancers, broad-proportioned black women who shake their butts while singing. Shake dancers are a storm on the chitlin ‘circuit but less welcome in Europe: he was booed at a Dutch festival, while his 2005 performance at London’s Barbican Hall had this newspaper’s critic condemning Rush as “ just pathetic. “

A year before his Barbican debut, where the predominantly white audience exuded silent discomfort, he had seen Rush perform in Mississippi before an almost entirely black audience that screamed, danced dirty and sang. It’s a cultural conundrum: there’s nothing unpleasant about their celebratory shows, but inevitably humor doesn’t always travel well. I mention the European criticism of his dancers, and Rush’s response contains moderate fury. “Shake dancers are from Africa,” he says. “It’s what black people do. The loot is part of our blackness and I am not ashamed of who I am or where I come from. “

Twerking, I suggest, comes from bobbing dancers. “You have it,” he replies. “Rappers love what I do because I’m quick with the lyrics.”

That said, Rush has toned down his act – his 2019 performance at London’s Jazz Cafe found him accompanied by a somewhat restrained bobbing dancer. It has also reshaped its sound: brilliant keyboards and soul styles have given way to elemental blues with Rush playing a magnificent harmonica. In fact, his 2022 shows were to be his first entirely solo concerts in Europe.

“In 1970, Rufus Thomas recommended that I remove the harmonica because Stax had told him it sounded old-fashioned,” notes Rush. “More recently I realized that there was a return to the roots of blues and so I went down that path. Less vaudeville, more authenticity. I wanted to show people where I came from … the sound I started with. “

In The Road to Memphis, Rush mentioned how, while dominating a large black audience, he hoped he could pass a white one. Now that he’s accomplished this, I wonder if he still plays the chitlin ‘circuit.

“I crossed but did not cross out, do you understand me?” he answers. “Some black artists, and I’m not naming names, cross paths and lose their people. I do not. I can still play a club in the black part of Memphis and attract thousands of people. Then I’m going to play Beale Street (the city’s blues tourist strip) and get a white audience. “

In his autobiography, Rush points out how he has always possessed more energy than anyone else and through our Zoom chat, not only does he speak with great enthusiasm, but he sings, plays the harmonica, and strums his guitar, anything but calling a dancer. His enthusiasm is infectious, this fun and funny retiree who radiates black pride and joy.

“A lot has changed in my life,” Rush says when asked about Black Lives Matter, “but a lot remains the same. Music has a link with freedom; it is a great place to bring people together, make friends, and understand each other. That’s why I keep dating. “

I Aint Studdin ‘is already a Hachette post.

www.theguardian.com

George is Digismak’s reported cum editor with 13 years of experience in Journalism