There is no more appropriate venue in which to stage a survey of post-second world war art in Britain than the Barbican in London. Like much of the painting, sculpture and photography on display, the arts center itself emerged out of the devastation of the second world war. Literally built on a City of London bomb site, it was also an ambitious attempt to come to terms with the destruction of the past and imagine a new future.

The mid-40s to the mid-60s are well known as the years when painters such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach came to maturity; when vividly realized photojournalism documented a battered and broken Britain, and brutalist architecture – of which the Barbican remains a storied example – went on to define the modern cityscape. But for curator Jane Alison, the period is due for a reassessment. The “rough poetry” – in a phrase coined by brutalist architects Alison and Peter Smithson – to be found in the art that emerged in these decades came, she says, from a much wider base that has usually been acknowledged.

While artists who had fled from Nazi Europe, such as Auerbach and Gustav Metzger, have long been included in the canon, Alison contends that the contribution of artists from the disintegrating empire who came to the UK is in need of deeper examination, as is the place of female artists in what was often a very macho scene. Importantly, this is a show of “art in Britain”, not “British art”.

“In some ways the art world then was welcoming,” says Alison, “and artists from overseas” – Frank Bowling, Francis Newton Souza and Aubrey Williams are among those on display – “arrived with a sense of optimism and a desire to participate. But just as in wider society, the art world was also infected by racism, antisemitism and sexism. Artists too often found themselves marginalized, pigeonholed and excluded from the bigger shows.”

Many of these struggles and stories are reflected in individual artworks such as Souza painting himself as St Sebastian or Magda Cordell’s proto-feminist focus on the female body as a subject of trauma. But Alison also sees continuities between artists operating in the same place at the same time. The “rough poetry” in her work often manifested itself in a concern with the vulnerabilities and resilience of the body, and with a sense of making something new after the destruction of war. More tantalizingly, there was a pervasive sense of “off-kilterness”, as Alison puts it. “All the old ideologies had been discredited and people were a bit at sea – everything was open to being reconsidered.”

There are obvious parallels between a sense of crisis then and now, as we grapple with the pandemic as well as emergencies around climate, refugees, equality and even the return of war again to Europe. During the run of the exhibition the contemporary artist Abbas Zahedi will seek to draw connections between the art on display and current anxieties through a series of works drawing on his projects in the fields of social practice, performance, writing and the moving image. “There is a comparable unease today to the convulsiveness that you see in the show,” explains Alison. “There is again a sensation of tumult that we have been once again thrown off balance. This exhibition is very much a project for our time.”

Postwar Modern: five key works

Break-off by Gillian Ayres, 1961 (main picture)

Female artists of the time had to struggle for recognition and Ayres was encouraged by tutors to move into traditionally female activities such as teaching needlework. This work sees a lighter, more colorful art emerging as we go into the 60s – but, says Barbican curator Jane Alison, “there’s still a kind of off-kilterness with the forms sliding off the edge of the painting”.

God Save the Queen (Hampden Crescent, Paddington) by Roger Mayne, 1957

Mayne, a self-taught photographer, made his reputation by capturing scenes of working-class children unselfconsciously adapting to the blighted environment around them. His starkly monochrome realism by him graphically illustrates the scars of war and also the prospects of building a new tomorrow.

Mr Sebastian by Francis Newton Souza, 1955

Souza was born in Goa in 1924 and brought up in Mumbai, where he was taught by the Jesuits. His work by him is full of Catholic imagery. Here is a sort of self-portrait of him as St Sebastian, painted after he moved to London. Souza encountered personal and professional difficulties in the UK and he depicts himself as not only assailed by arrows but also constrained by that most symbolic item of western conformity, the business suit.

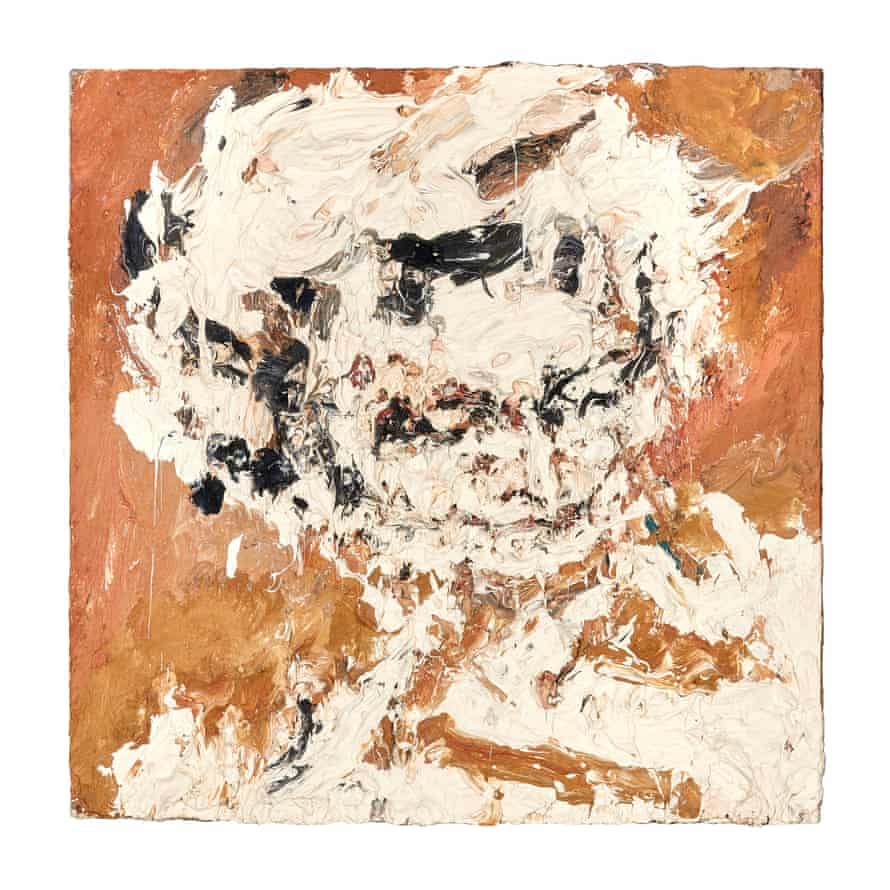

Head of Gerda Boehm by Frank Auerbach, 1964

Auerbach is known for working with a small group of sitters for portraits, including his cousin Gerda. His painstaking process of him, involving multiple removals and reapplications of paint, results in a visceral and intense depiction of his subjects of him. Auerbach was just eight when he was sent to London from Berlin in 1939 – his parents remained in Germany and were later murdered in the concentration camps.

Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965 is at Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 26 June.

www.theguardian.com

George is Digismak’s reported cum editor with 13 years of experience in Journalism