During a CBS “60 Minutes” interview that aired on Sunday, President Joe Biden said the SARS CoV-2 pandemic was over. The most remarkable thing about his words from him might be that many people will believe, or worse, amplify, them in the most literal sense.

After all, our country was already in a place where there could be substantial disagreement on whether the nearly 65,000 preventable Covid-related deaths to date since April 30 — around when deaths from the massive BA1 omicron variant arise subsided — could constitute the pandemic being over .

If Biden was referring to the emergency phase of the pandemic being over, his statement is in some ways correct — at least for now.

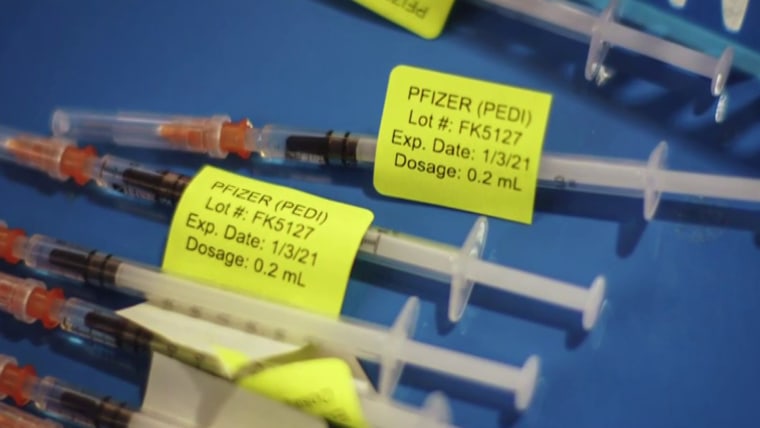

If Biden was referring to the emergency phase of the pandemic being over, his statement is in some ways correct — at least for now. This is largely because the health care system is not currently overwhelmed by Covid patients, vaccines are widely available (including for children), there are substantial levels of hybrid immunity (for the moment) and we have very effective prophylactics and treatments for those who are vulnerable to a severe outcome.

However, we are still dealing with a crisis. Even though Biden also said that “we still have a problem with Covid,” if he’s saying the pandemic is over, it becomes unclear what the scope of the remaining Covid problem is and what exactly needs to be done about it.

One glaring issue that remains and what Biden’s comments grossly missed the mark on is post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection, commonly known as long Covid. According to June data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it affects about 20% of the millions of people in the US who’ve had Covid.

Even with its long Covid plan, the administration has not instituted any better policies or efforts aimed at reducing the future public health burden of the condition. When you think about how debilitating long Covid can be — fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, chest pain, shortness of breath are just some of the symptoms — it is clear why addressing it as an economic crisis as well as a public health crisis is crucial . In August, a report by the Brookings Institution suggested that up to 4 million people may be out of work because of lingering symptoms. Others currently working who already have long Covid or who eventually develop it may have to go on disability at some point.

The magnitude of the long Covid problem may be larger than most people realize.

With major public health problems, especially new ones that are poorly understood in terms of burden, causes and risk factors, it is critical not only to collect data but to set up what is called a public health surveillance system. The CDC defines public health surveillance as the “ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those responsible for prevention and control.”

In an important development this month, it was announced that research investigators from the Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University’s schools of medicine and public health received a five-year $9 million grant from the CDC to mine statewide electronic health records to estimate the incidence and prevalence of long Covid in Indiana.

However, we don’t yet have a national population-representative surveillance system for long Covid in the US For a condition like this, such a system could not rely solely on data from people who access the health care system. The UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) has had a model long Covid surveillance system in place since February 2021. Its September 2022 data shows that as many as 3.1% of the entire UK population may currently have long Covid. The office conducts routine, population-representative surveys that ask those who have had the virus: “Would you describe yourself as having ‘long COVID’, that is, you are still experiencing symptoms more than 4 weeks after you first had COVID-19, that are not explained by something else?”

To begin to shed more light on the extent of the long Covid problem in the US and who is most affected and at risk, our team at the City University of New York recently completed a representative study on a sample of 3,000 US adults. We asked a question similar to the ONS’ to draw a comparison, and we found that 7.3% of US adults (about 18.5 million people) likely had long Covid in early July 2022, which is a staggering and sobering number.

Why is the current prevalence of lingering symptoms in the US higher than that in the UK, given relatively similar pandemic experiences? It could be due to higher and earlier vaccine and booster uptake in the UK versus the US It could also be that in the UK there were fewer infections and better coverage of vaccines and boosters among those who we have since learned are at higher risk for long Covid (eg, women and those with comorbidities).

Indeed, an increasing body of evidence, consistent with our recent study, suggests that being up to date on vaccines substantially reduces the risk of developing long Covid following a breakthrough infection. This is huge and welcome news. But if the leader of the US is saying that the pandemic is over, motivation for people here to get a vaccine or booster will continue to wane. Booster levels have remained low when compared with levels in the UK and have been slow to increase in recent months. With no diagnostics or treatments for long Covid, preventing it from occurring is all the more critical.

The CDC still uses the term “fully vaccinated“ to describe people who have received two doses of an mRNA vaccine when it should be referring to them as undervaccinated and vulnerable to a severe Covid outcome, including long Covid.

Not unrelated to this problem, the CDC still uses the term “fully vaccinated“ to describe people who have received two doses of an mRNA vaccine when it should be referring to them as undervaccinated and vulnerable to a severe Covid outcome, including long Covid. Because the president’s statement on the pandemic was similarly unclear, any important distinction or context that was intended was unfortunately lost on the public.

Clarifying where we stand on Covid needs to include an active and targeted approach to increase vaccine coverage among those most at risk, coupled with better targeting of rapid antiviral treatment for those who become infected. But the US has become passive about promoting vaccines and boosters.

And given the magnitude of long Covid and how little is known about who is most affected and at risk, the CDC needs a formal national surveillance system to monitor it. The CDC’s and Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey began collecting data on long Covid in June. Similar to our study, the survey estimated that 7.6% of US adults were experiencing long Covid symptoms as of July 2022. Critically, public health surveillance goes well beyond data collection and analysis to include generating and sharing of information for action with all those who need to know.

We see this information sharing happening clearly in the CDC’s Covid Data Tracker, where key metrics from Covid-19 surveillance are displayed, including daily data on cases, deaths, hospitalizations and vaccination. Displaying long Covid metrics and related trends on the Covid Data Tracker would be helpful. Data from the national Household Pulse Survey could be used for this, and it is a large enough survey to be able to provide very detailed geographic breakdowns for state and local health departments to use. Elevating long Covid tracking in this way could substantially increase the country’s focus and potential for collective programmatic and policy action on this critically important dimension of the pandemic.

While we may be out of the emergency phase of the pandemic — thanks to some amazing scientific advances and a sustained absence of any new variants of concern — we are not yet out of the woods. On average, to date, we are still experiencing more than 31,000 preventable Covid-related hospitalizations daily and nearly 500 preventable Covid-related deaths per day.

When it comes to the SARS CoV-2 pandemic response going forward, the CDC must leverage surveillance to focus on the whole public health threat posed by the virus, including long Covid.

www.nbcnews.com

George is Digismak’s reported cum editor with 13 years of experience in Journalism