“Heading south,” ordered the captain.

“But, Captain, there are no addresses in space.”

“When you travel towards the Sun” –replied the captain- “and everything becomes strawier and warmer and apathetic is that you are going in that direction. South.”

Ray Bradbury

‘The golden apples of the Sun’

In his short story – three pages – published in 1953, Bradbury recounts the first expedition of a manned ship to collect a sample of the Sun. It is not a “hard” science fiction story and, in fact, some concepts do not hold; just a poetic reflection remotely based on the myth of Prometheus. Three-quarters of a century ago, before the first artificial satellite flew, any fantasy about space was acceptable.

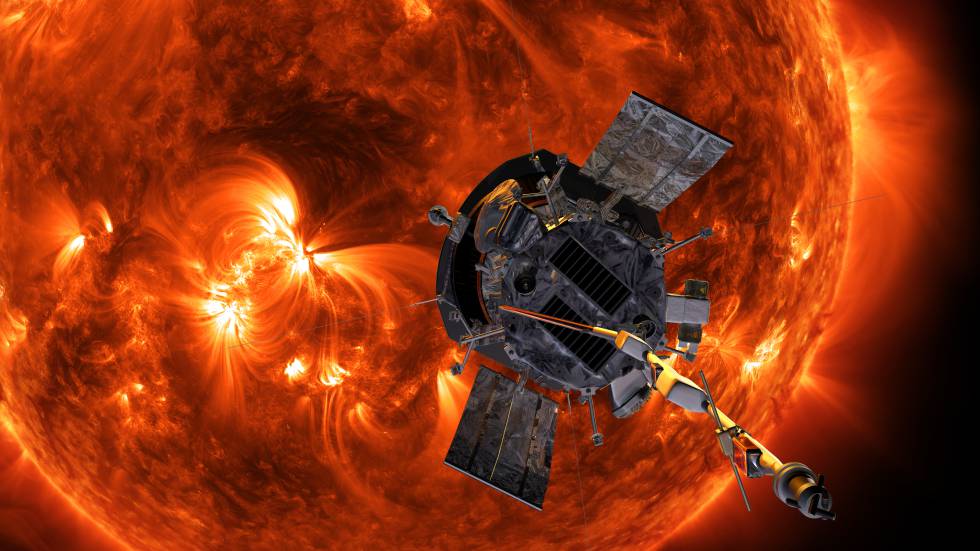

Today, the fantasy has come true. At the end of November NASA announced that its probe Parker it had touched the Sun. At least its atmosphere. At a height above the photosphere (the layer generally considered the “surface” of the star): 8.5 million kilometers or only twelve solar radii. And it did so by moving faster than any human-made object, at nearly 590,000 kilometers per hour. And it continues on a gently spiraling path that by 2025 will take it up to less than 6 million kilometers.

The surface temperature of the Sun is about 5,600ºC. Enough to melt almost any material. How can a probe withstand such punishment without disintegrating? In part, thanks to the thermal shield that it always keeps directed towards the Sun. All the equipment on board are crouched behind that protection. Even the photoelectric cell panels, which are only fully deployed when the ship moves through more remote regions.

The shield itself is a carbon foam sandwich only half a span thick between two sheets of the same material. The side that is to receive the radiation is covered with a layer of white ceramic, to better reflect the heat. In the moments of maximum approximation it reaches 1,300 ºC, more than the lava from the La Palma volcano.

All the materials on board are special to withstand extreme temperatures. The copper normally used in electrical cables would melt; instead, conductors made of niobium are used, protected by sapphire crystal sleeves. The Faraday cavity, the only sensor that peeks above the shield to see the Sun directly, is made of an alloy of titanium, zirconium and molybdenum, which would withstand up to 2300ºC.

Inside the sensor there are electrodes designed to separate the solar wind particles according to their energy levels. They are made of tungsten, the metal with the highest melting point, above 3,400ºC. These materials are typically machined with laser cutting tools; in this case even that was not enough and they had to be shaped by attacking them with acid.

Testing the operation of these equipment in real working conditions was not easy. To simulate the light and heat of the Sun, IMAX cinema projectors were used, modified to give even more intensity and at the same time, a particle accelerator reproduced the impact of the solar wind. Not content with that, the main sensor was tested once more in Odiello’s solar furnace, on the northern slope of the Cerdanya, concentrating on it the light reflected by ten thousand adjustable mirrors.

The Sun is a huge ball of plasma that, of course, has no solid surface. What we see is the glow of the photosphere, a relatively thin layer, where huge plumes of incandescent gas bulge rising from the depths. Intense magnetic fields twist on them and occasionally colossal flares are produced that follow the path marked by the lines of force. Above it, the corona, so faint that it can only be seen when the Moon hides the disk of the Sun.

It is difficult to say how far the atmosphere of our star reaches. The crown expands and contracts following the evolution of the star’s activity. Its limit was estimated between 10 and 20 solar radii. At about that level, the pressure of the radiation drives the ionized hydrogen and helium atoms so energetically that they are freed from gravitational pull and local magnetic fields. Subatomic particles escape into space at enormous speeds, forming the solar wind.

Last April, the Parker probe was finally able to fine-tune those measurements. When it was about 18 solar radii, its instruments detected a region of intense turbulence. It is not a soft limit but has enormous ups and downs depending on solar activity. In fact, as it got closer and closer to perihelion, the Parker went in and out several times on the crown. As expected, he detected a large increase in magnetic fields, sharp zigzags in the magnetic field lines and also areas of intense disturbances in the plasma, followed by much calmer ones, such as when entering the eye of a hurricane.

That transition, theorized in the 1940s by the Swedish Hannes Alfvén, marks the fuzzy border between the atmosphere of our star and outer space. It is curious that both his theories and those of Eugene Parker (who in the mid-50s foresaw the existence of the solar wind) were rejected by the scientific community of the time, calling them little less than heretical. The recognition of both took a long time to come: the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for Alfvén and the baptism of the solar probe for Parker. It is the first time that NASA has given one of its spacecraft the name of a living scientist.

We are emerging from the low of the eleven-year cycle of solar activity. As this increases, the size of the crown and probe will also increase. Parker more and more time will be spent inside the atmosphere of our star. For now, after perihelion, it is gaining height again towards the calmest orbit of Venus. As the captain of Bradbury’s tale would say, “heading North”

You can follow MATTER in Facebook, Twitter e Instagram, or sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter.

elpais.com

Eddie is an Australian news reporter with over 9 years in the industry and has published on Forbes and tech crunch.