When the Atocha area of Madrid was recently undergoing construction, Twitter commented with surprise that rails were sprouting from the asphalt: they were the memory of the city’s past, when its inhabitants moved from one place to another using the trams. And the truth is that Madrid is not the only town in which the modernization of the streets discovered forgotten routes: when one of the avenues in the center of Vigo was built a few years ago, its inhabitants stumbled upon the rails of the old service that linked the neighborhoods of the city and even reached the periphery.

The history of the success and failure of the tram is relatively recent, although perhaps it has remained somewhat blurred in the collective memory.

This means of transport had already begun to be considered in the mid-19th century, when it worked with animal traction (despite the fact that it already circulated on roads), although it was after its electrification at the turn of the century when it became the emblem of urban life. and of the new. “The tram was closely linked to the idea of modernity,” says Carlos Larrinaga, a professor in the Department of Economic Theory and History at the University of Granada.

In Spain, the tram arrived in its first identity – the animal one – a little later than in other European cities, but in its second – the electric one – it did so with only a slight delay, explains the expert. Even so, the professor indicates, “it was not such a widespread phenomenon” among Spanish cities. In order for cities to have a tramway, they needed to have a large enough mass of population to make it profitable – it was a private company: an investor jumped in to offer the service – and also with growth that made it necessary.

For this reason, as the historian points out, its appearance is connected with the expansion of the cities themselves, in which it was necessary to travel greater distances. “It was popular, but in some cases it was not cheap,” says Larrinaga. Even so, to move in the new Barcelona or Madrid, it seemed inevitable to take it. “The alternative was to move 5 or 6 kilometers,” he says.

Trams at Puerta del Sol in Madrid.

ABC file

At first glance, making a census of which cities did or did not have a tram is complex, because in some of them it did not last for a long time. In others, despite having a large population for the time –it was, for example, the case of Burgos, where the historian explains that there were projects, but they never got under way– this method was not used. Of transport.

“It depended on many things”, such as whether the city had a rich dynamic in terms of business and urban life (key, for example, in cases such as San Sebastián), that there were investors determined to launch the service and that you are in an urban environment. Population growth helped. “In Vigo, for example, in 1896 there was no tram,” says the historian. Then the city had about 23,000 inhabitants. In 1917 the number of inhabitants had practically doubled and the tram was already running through the streets.

In 1917, in the still golden age of the tram, it circulated through 24 Spanish cities, calculates Carlos Larrinaga. Vigo, Valladolid, Madrid, Barcelona or Seville were some of them. “In the case of Madrid, the tram network reached its maximum extension in 1954, just a few years after its municipalization, reaching 188 kilometers of network,” adds Adrián Fernández Carrasco, managing director of the Spanish Railways Foundation.

Although it had reached its maximum expansion in the 50s, the Madrid tram did not have much time to live. It was something in which the Spanish cities showed a similar pattern: in all of them, the service ended up being eliminated and infrastructures were dismantled or buried under the asphalt of the streets.

And this was not happening only in Spain –where, on the other hand, the tram had ended up becoming a municipal service– but it was something generalized to western cities. Only in exceptional cases has this method of transportation survived uninterrupted to the present.

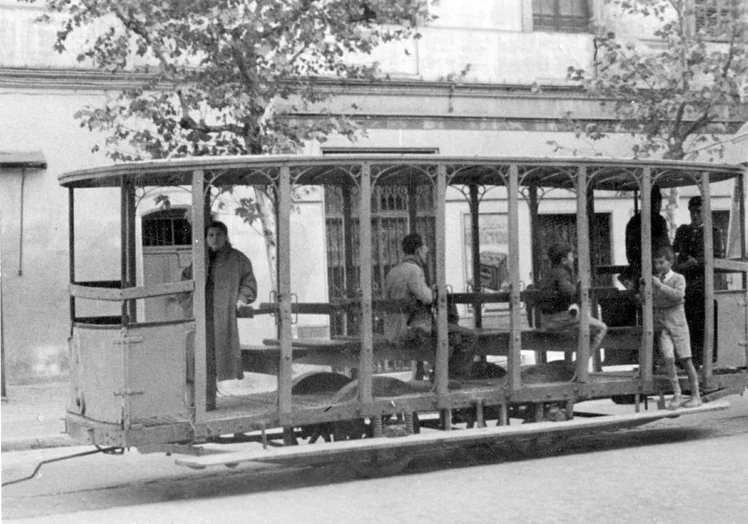

The first trams that circulated at the beginning of the century in Seville were completely open.

ABC file

But what led to the disappearance of the trams? “To a large extent, it was due to competition from motor vehicles,” says Larrinaga. The vehicles ended up becoming popular and traffic problems began to appear.

“In this context, the tram was perceived as a hindrance to the fluidity of circulation, as an element of the past compared to the bus or the metro, modes that ‘annoyed’ the car less”, Fernández Carrasco points out. The more traffic on the streets, the more problems the tram had to circulate, which shared them with cars and buses.

“And the worse the quality of the public transport service, the more tram passengers decided to leave it and get in the car, which exacerbated the worsening of the public transport service, which also needed to be subsidized”, explains Tomás Ruiz Sánchez, Professor of Transport from the Polytechnic University of Valencia. “This process is known as the ‘vicious circle’ of public transport,” he summarizes.

The bus could also do something that the tram could not: change its route to adjust to the new urban needs.

As had happened to the tram a few decades before, the vehicles became the element of progress. “Thus begins a political campaign that encourages the rejection of the tram by the population, which had its most unfortunate reflection when, during the last day of tram circulation in Barcelona, the population assaulted and destroyed the vehicles”, points out Fernández Carrasco .

“The bus is beginning to be seen as a symbol of modernity and the tram as something of the past,” says Larrinaga, who recalls that then not only was there not the same ecological awareness as today, but also that oil prices were very low. “Between 1964 and 1972, ten large Spanish cities saw the trams disappear from their streets,” says Fernández Carrasco. After living with the new fashionable medium, they ended up being replaced by it. By the 1970s, the car had won the game.

Tram in the city of Alicante, today.

“Experience has shown that it was a disastrous mistake to dispense with efficient public transport on the surface to favor the private car”, summarizes Fernández Carrasco.

The death of the tram was not, perhaps for this reason, definitive. Experts recall that Valencia was the first city in Spain to recover it, opening in 1994 the line that runs to the Malvarrosa. Almost 30 years later, she is not alone. Bilbao, Barcelona, Alicante or Zaragoza have once again put trams –or, as Ruiz Sánchez recalls, “light rail”– on their streets, in a process that is also global. Bordeaux, Paris or London are some of the European cities that have resumed these services.

The ‘revival’ of the tram is explained by its greater sustainability, but also because the star means of urban transport of 100 years ago solves many of the problems of present-day cities.

The modern tram alleviates “the problems of congestion, noise and space occupation”, as Fernández Carrasco points out. Now they are bigger and with more passenger capacity; and they have their “own path”, indicates Ruiz Sánchez, which prevents them from using the same spaces as the rest of the traffic and gives more “quality of service”. “In addition, in most cases it was used to improve the urban environment and redevelop run-down areas,” he adds.

Even so, the tram is not a panacea. Ruiz Sánchez recalls that it is necessary to build an infrastructure and assume the maintenance costs – “a tram is 10 times more expensive than a hybrid bus and five times more than an electric one”, he points out – so for it to have a positive impact on the sustainability of mobility “it must be widely used, with a high occupancy rate”.

For this reason, the expert outlines medium and large cities, with high population densities and “with policies that clearly support sustainable mobility”, as the spaces that could successfully reincorporate the tram.

www.hoy.es

Eddie is an Australian news reporter with over 9 years in the industry and has published on Forbes and tech crunch.