When the coronavirus struck New York City in March 2020, an unprecedented number of tenants stopped paying rent. Many just couldn’t afford it. Others demanded better conditions in their buildings. And some saw it as a way to call for structural change. This informal movement, organized around a call to “cancel rent”, was buoyed by a nearly two-year eviction moratorium, enacted to protect New Yorkers from losing their homes during the pandemic.

But with the moratorium expiring last monthHave New York’s tenants recovered, or are they at risk of losing their homes?

We spoke to more than a dozen people across New York City who stopped paying rent or went on rent strike since the pandemic began. We wanted to listen to the city’s most precarious residents as they fought – and still fight – to hang on to the roofs over their heads. Most had applied for housing assistance during this time, but none had yet received aid.

All described how they had gained a deeper appreciation for collective action, and all know their battles are far from over. Below are five of their stories.

Rose Hellesca, 42, Brooklyn

Rose Helesca was at a breaking point. Not just from her work de ella as a nurse on the frontlines of the pandemic – but from living with her three children in one of Brooklyn’s most neglected buildings, 1616 President Street. Even before the virus hit, the ceiling leaked, the walls were moldy, the heat hardly worked, and rats and roaches roamed free. She didn’t know whom she was angrier at: her landlord, Jason Korn, who ignored the residents’ complaints, or New York’s housing department (HPD), which seemed unable to hold him accountable despite him topping the list of the city’s “worst landlords” two years in a row.

So when her neighbors decided to start a rent strike to demand changes, Helesca was all in: “We said, ‘Let’s hit his pocket.’”

It was the city’s first organized rent strike under the pandemic, and it got Korn’s attention. He began calling tenants to negotiate, offering payment plans and individual fixes. But the tenants held firm in demanding top-to-bottom repairs. Then, in the summer, says Helesca, the landlord turned the heat up, forcing all the tenants outside. When they called Korn to complain, Helesca says he replied: “What’s the big deal? You’re not paying rent, so what are you complaining about?”

In an email, Josh Rosenblum, a lawyer representing Korn, called the story about the heat “an absolute lie” and blamed the building’s outstanding violations on tenants refusing access to their apartments for repairs. In September 2021, Korn sold the building to a newly created holding company; Helesca says tenants have never met the new landlord, but they suspect Korn is behind the company, which Rosenblum also denied.

The standoff is approaching two years with no resolution, but Helesca feels more determined than ever. They’ve inspired tenants of Korn’s other buildings, who have started rent strikes of their own. “The other buildings believe in us – they’re like, ‘1616 is so powerful.’”

Helesca said she hoped more tenants would realize they can stand up to their landlords. “Don’t be afraid. Fight for what you think is right. As my mama says, there’s nothing to be scared of if you know you’re not wrong.”

Caitlin Baucom, 37, Brooklyn

The first time the artist and activist Caitlin Baucom received an eviction note after they fell behind on rent for their Bushwick loft in 2019, it felt “terrifying”, they said, “like the floor was falling out from under you”. But it was a gift in disguise. As Baucom researched housing laws, they realized the note from their landlord, Richard Pogostin, was likely to be illegal – along with many other aspects of his management of the building. So when the pandemic hit the following year, they felt empowered to stop paying rent for good. “I was just like, ah, fuck it,” they said. “I don’t think they can legally proceed with an eviction because their half is also illegal.”

That summer, after a gym vacated the storefront under their apartment, Baucom and other volunteers entered the space and transformed it into a mutual aid hub against their landlord’s wishes. For a while, the Gym, as the operation became known, distributed support kits to Black Lives Matter protesters, as well as meals and supplies to neighborhood residents and unhoused people – until Pogostin force them out with the aid of police. Since then, the volunteers have continued to help their neighbors from the sidewalk.

In a phone call, Pogostin called Baucom’s complaints about the building maintenance “ridiculous” and said he would continue efforts to evict them. He said Baucom’s mutual aid was “all about them not having money, needing a place to stay, and somehow turning it into a social issue”, and their sidewalk activities were “hurting business and scaring people”. It was people like Baucom, he said, who were driving New York’s rents up by forcing others to subsidize them.

But Baucom argues that not paying rent does precisely the opposite, by refusing to feed the cycle of speculation that drives rents up in the first place. And people with more privilege should join in, they say.

“In my opinion, the mutual aid thing and the rent strike thing and the active resistance of capitalism is all the same thing,” they said. “It shouldn’t be incumbent on people who can’t afford to pay rent right now to rent-strike. The point should be that everyone rent strikes or refuses to pay above a certain amount of rent so that then their neighbors can also have homes.”

Shy Morris, 48, Brooklyn

Virtually every dollar Shy Morris receives – from her disability checks, social security and odd jobs – goes toward her apartment. That means nothing left over for food, and sometimes not even her phone bill from her. “I’m just afraid because I don’t want to be homeless,” she said. With the eviction moratorium over, she doesn’t want to take any chances.

Morris’ one-bedroom co-op in Fort Greene was left to her by her grandmother, who owned the unit and passed away shortly before the pandemic. But the virus hit, Morris lost her job as a home attendant, and that’s when she stopped paying her apartment’s monthly maintenance fee – which “kept piling” until it had reached more than $8,000. A member of the co-op board approached Morris and threatened her with eviction: “You can’t just stay in this apartment. You’ve got to give something.”

Now Morris pays the monthly maintenance but relies on a neighborhood mutual aid group to buy food and other necessities. “They really saved my life,” she said. “Food stamps are OK, but sometimes you need cash. Tissues, soap, you can’t buy these things with food stamps.” To give back, Morris volunteers her free time to help with food distribution. It’s become a community for her. “It’s a place where you can come and be elbow to elbow with people. I like that we can sit, and talk and chill, even if it’s just for the few minutes, the few hours.”

Ramona Ferreyra, 41, the Bronx

When Ramona Ferreyra decided to stop paying rent, it wasn’t just because her apartment was in disrepair. For her and her neighbors de ella in Mitchel Houses in the Bronx, it was about saving public housing. “Lawyers will tell us, do you just want to sue for repairs? And I’m like, ‘No, I’m looking at big systemic issues,’” she said.

Ferreyra, a former government employee, wants a class action lawsuit against the New York City housing authority (NYCHA), which owns and maintains the city’s deteriorating public housing buildings. She alleges that the housing authority’s chair, Greg Russ, has purposely allowed apartments to degrade as part of a plan to privatize them.

Under Russ’s plan, called the “Blueprint”, NYCHA would transfer as many as 110,000 NYCHA apartments from section 9 – federal public housing – to section 8, a federal voucher program. To qualify for the vouchers, NYCHA would have to declare those units “obsolete”. It could then raise money for repairs by issuing bonds to private investors against those vouchers, using the properties as collateral. Russ says this method could raise as much as $6 for every dollar of federal funding.

Ferreyra argues this would effectively kill public housing, as the debt would leave the buildings vulnerable to the investors, who would have far less reason to guarantee tenants’ rights.

Under section 9, tenants enjoy federal protections, including a rent capped at 30% of their income, a right to organize and eviction protections. “In these spaces, we’re able to thrive and use flex, our imagination and our capacity because you have the safety net of housing,” she said. “So that’s why you have a Nas, that’s why you have a Jay-Z, right? These spaces are incubators for people not to be worried about, ‘Am I going to get evicted next month?’”

Marina Quiróz, 62, the Bronx

Four years after renting her first apartment, Marina Quiróz still doesn’t have a key to her building’s entrance – and that’s far from the worst thing about it. The building is filthy, leaky and constantly breaking down; in the freezing winter, the heat comes on once or twice a day for 15 minutes. The elevator doesn’t work at least three days a week.

But nothing has affected her as much as getting harassed by her landlord and superintendent after she lost her hotel cleaning job in March 2020 and could no longer pay rent. “They called and called and came to knock on my door all day and night, sometimes at 9pm,” she said. “The stress was killing me because I didn’t know what to do.” She fell sick from her anxiety, developing hypertension, heart palpitations, dizziness, and pain in her shoulder. Soon, the medical bills started adding up, too.

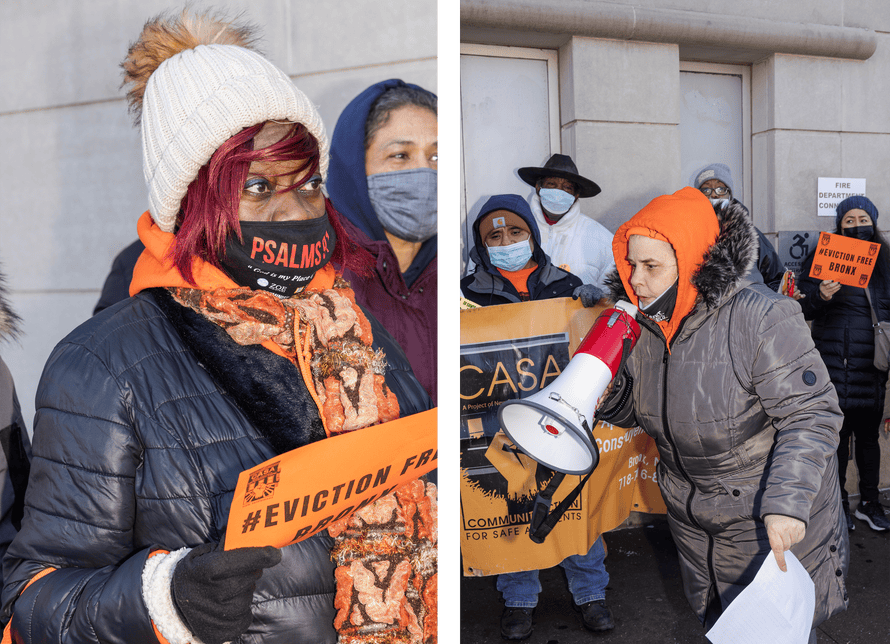

She finally felt relief after meeting members of Community Action for Safe Apartments (Casa), a Bronx non-profit. “I started visiting the office, and I felt there was human warmth,” she said. “I began to know my rights as a tenant. I thought that if something was damaged and the landlord and super didn’t fix it, then I couldn’t do anything. I found out that I can claim my rights, demand them.”

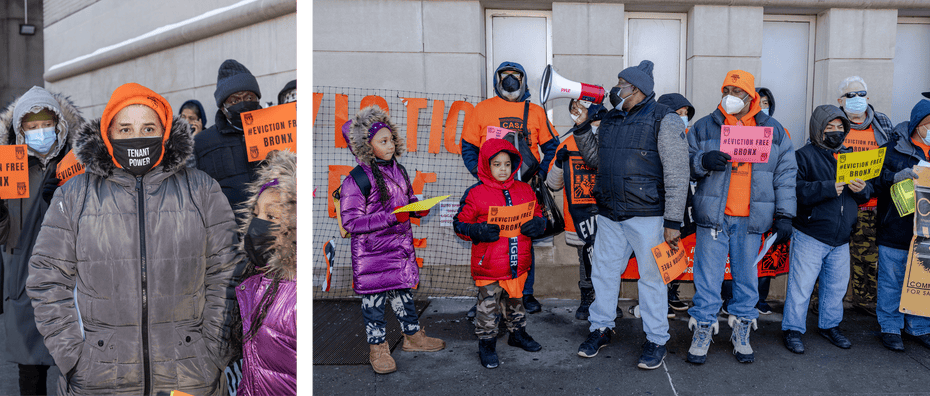

On 1 February, the first day her rent was due following the eviction moratorium’s end, Casa announced it would launch an anti-eviction campaign in the Bronx, where 40% of New York City’s evictions occur. Pablo Estupinan, the group’s lead organizer, said that in addition to launching an “eviction defense network” to educate residents about their rights, they would start performing eviction blockades: physically blocking marshals from carrying out evictions – at tenants’ request.

Estupinan expects the campaign to go on for years. “It’s been normalized for thousands of people to be evicted, and our job is to stop that. We’ve seen it’s possible with the moratorium.”

Now, Quiróz plans to stand in front of the governor’s office and demand an extension of the moratorium until June. “We have to make ourselves seen by the authorities. What are we going to do on the streets during this awfully cold winter? We have to protest, we have to continue with this fight.

“We there need help. It’s not just me, Marina Quiróz, it’s the entire city.”

www.theguardian.com

George is Digismak’s reported cum editor with 13 years of experience in Journalism